Now, take each of these questions one by one, and consider the implications before moving on to the next.

Do we let newspapers go out of business?

Let's say that the New York Times, Chicago Tribune and The Wall Street Journal are all that remains of a once highly-penetrated news media market. Would we consider government loans to keep them alive? Are they, either collectively or individually, too big to fail?

What if it was down to just one remaining publisher? And what if that last one standing announced it would be letting go of 90% of its reporters?

What if it files for bankruptcy and makes plans to close shop for good?

And what if we let it?

We demand information to be free, accepting ads as a sort of coverall for our distaste of paying for things we find of value, but also using ad blockers because, well, who wants to look at ads? Yet a quick informal poll confirmed for me that we deem it absolutely necessary that reputable news coverage is available on an ongoing basis. How do we ensure that reports keep reporting and that news is held to some kind of a standard?

The worst case scenario (in regards to news) might be the following:

All reputable news publishers shut down, and give way to rising crowd-publishing sites of supposed and unverifiable eyewitness testimonies with no professional filter or attempt at eliminating bias, and uninformed articles that would be considered opinion pieces today but are touted as fact instead. Boycotts and fake news accusations fill our lives like the Salem Witch Trials and consume our news feeds rather than focusing on the things news should be covering like the economy, business, politics, culture, etc. Articles written by robo-journalists are also prevalent, a practice that started with the coverage of local sports and less popular Olympic games when the money-making reputable news organizations were still up and running, but has long been bastardized into a way of automatically filling the internet with propaganda about whatever it's originator wanted to promote. Some sites will tout their efforts to stem the auto-propaganda while others will embrace it as an intelligent technology that is only feeding off our data of what we click on to give us more of the same crap it thinks we want based on our usage history. We don't know what's real and what's fake anymore, and really, it's all fake to an extent because the coverage is so slanted and misrepresented - like when you played "Telephone" as a kid and the message got skewed the more it was repeated until it is completely unrecognizable and absurd.

Articles written by robo-journalists are also prevalent, a practice that started with the coverage of local sports and less popular Olympic games when the money-making reputable news organizations were still up and running, but has long been bastardized into a way of automatically filling the internet with propaganda about whatever it's originator wanted to promote. Some sites will tout their efforts to stem the auto-propaganda while others will embrace it as an intelligent technology that is only feeding off our data of what we click on to give us more of the same crap it thinks we want based on our usage history.

We don't know what's real and what's fake anymore, and really, it's all fake to an extent because the coverage is so slanted and misrepresented - like when you played "Telephone" as a kid and the message got skewed the more it was repeated until it is completely unrecognizable and absurd.

The loop of misinformed news becomes so overwhelming that we just shut it all off, unsubscribing for all alerts, disliking all articles on social media, and we stop searching for answers about current events or topics we care about because we just don't have a reliable way to determine what is fact and what is fiction. We give up on understanding the world around us, and try to content ourselves with living our day-to-day lives and just generally trying to tip-toe around anything that could possibly happen.

The richest 1%, of course, will hire a new kind of private investigator of sorts to research what is real and definitively advise on what their employers should be concerned about. They will have a huge leg up on the other 99% who can't afford to pay these premiums and have to suffer through misinformation or pay specialists for the specific kind of advice they need at the moment without learning about anything else that is really going on. These specialists will make it their business, literally, to be in the know about changes in law, the economy, culture, finance, etc., and will charge by the hour for doling out the same advice to 50 different clients per week, where they could have lowered their costs by publishing it to a subscriber base that would reach a much larger audience - but that wouldn't bring in sufficient profit, we tried that, remember?

Maybe, as the circular thinking above suggests, it will be an issue of supply and demand, and as supply for reliable news coverage diminishes, the market will step up and become more willing to pay for their news, and the news market will find a new equilibrium in a purely-online basis.

Maybe the use of automation will instead improve the efficacy of the human reporters, exponentially shrinking the number of reporters and editors needed while still sustaining our beloved reputable sources of news at a much lower cost. Then, do the remaining reporters get paid really well, like millions, because they are the remaining hold outs who have successfully navigated the layoffs and learned to collaborate the most effectively with the robo-reporters? Or do

they get paid minimum wage because there are 100,000 other unemployed reporters who'd happily take their job (and could do so easily because of the brilliance coming from Artificial Intelligence rather than the employed reporter)? Either way, this might feel like a small victory for society, but if this happens to 99% of jobs in America, or even 50%, we'd be looking at the highest unemployment rates in history, far worse than the Great Depression or even agricultural days.

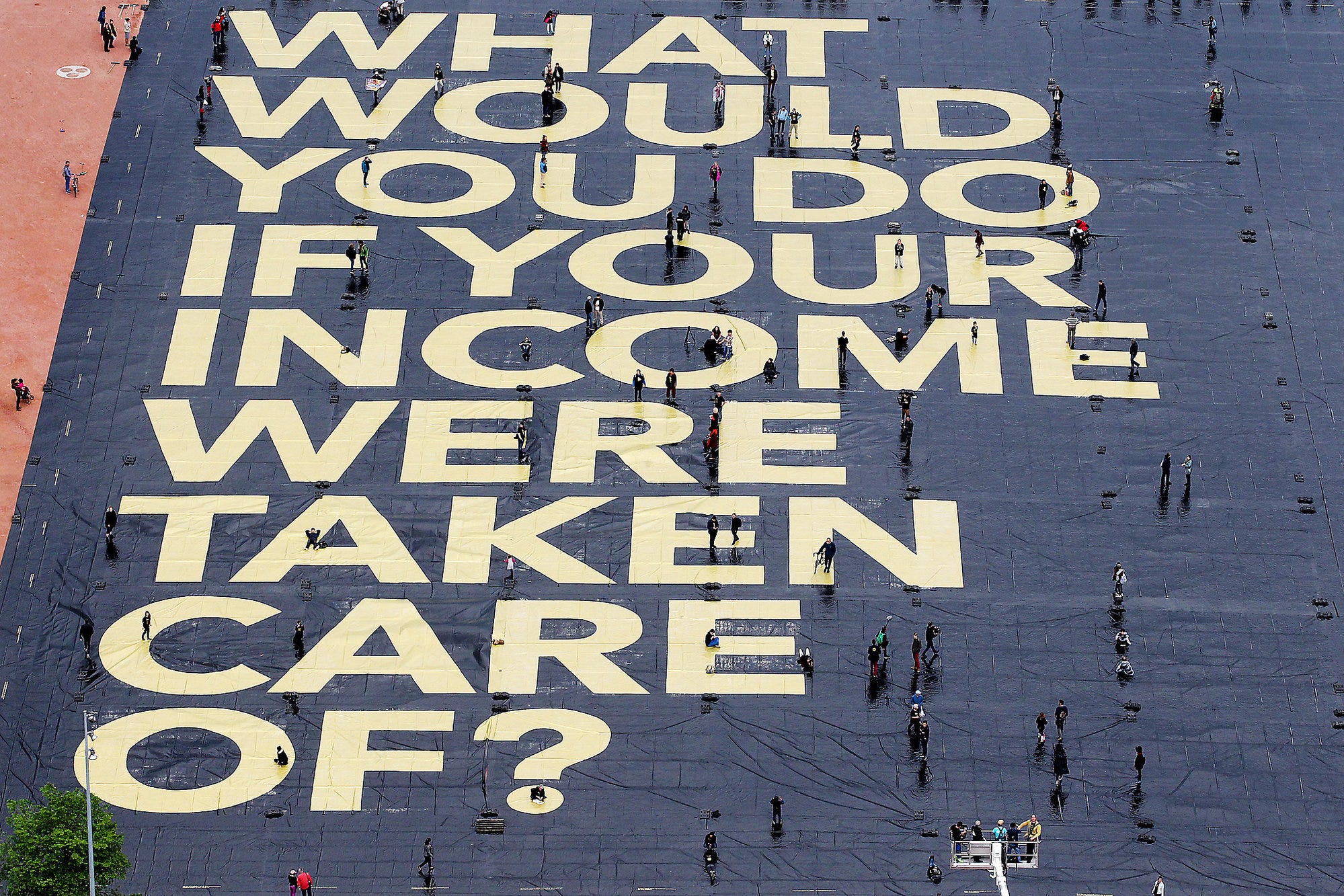

I've been reading a lot lately about two related up-and-coming topics: technological unemployment and the universal basic income. By my casual definition, technological unemployment is basically where robots or artificial intelligence-powered computers either replace or greatly subsidize the jobs most people do, diminishing the need for human workers in potentially drastic and devastating waves until maybe 30% or maybe 1% of what used to be the work force have traditional or non-traditional forms of paid work. What to do with all those unemployed people is the paradox that only seems to have one answer in my research: a minimum payment regardless of employment status or contribution to society that is capable of keeping all citizens (just barely) above

the poverty line, a universal basic income, or UBI. Sound expensive? I thought so too! But then, we also spend unimaginable amounts of money on programs like welfare, and you hear anecdotes about people cheating the welfare system and living better than people who are working. Then there's all the bureaucracy and administration of such programs, people having to accept and evaluate application forms and determine which cases are worthy, and then having to follow up with people on welfare to make sure they're fulfilling some pre-determined obligations in order to maintain their welfare status. Sure, by having all this administration, we're giving government employees jobs, but we're also maintaining a system that keeps people down and discourages getting better jobs or working harder.

the poverty line, a universal basic income, or UBI. Sound expensive? I thought so too! But then, we also spend unimaginable amounts of money on programs like welfare, and you hear anecdotes about people cheating the welfare system and living better than people who are working. Then there's all the bureaucracy and administration of such programs, people having to accept and evaluate application forms and determine which cases are worthy, and then having to follow up with people on welfare to make sure they're fulfilling some pre-determined obligations in order to maintain their welfare status. Sure, by having all this administration, we're giving government employees jobs, but we're also maintaining a system that keeps people down and discourages getting better jobs or working harder. Previously calling myself a Republican, and then changing my tune to economic conservative with liberal views in other areas, it's been a tough internal battle for me to see universal basic income as anything but a communist fairy tale, but I do now, and I would caution any skeptic not to dismiss it casually as well. I'm still not completely sold on the idea myself, but it's the best alternative to our current path that I've found. I could be persuaded of a better alternative, in fact, I'd prefer one, I just don't know what that would be. So for now, I'll use UBI as a possible solution that we should consider.

But before we jump to the solution, let's start with the problem which stems from technological unemployment. If it wasn't a concern, then UBI has a lot less to stand on. But I'm pretty convinced that it's already a little problem, and it's going to be a bigger problem in the future. I think the biggest counter-argument to technological unemployment is that, in the past when technology replaced human power, we were freed up to do other things and created new jobs that couldn't have been envisioned previously, and so the expectation is that as robots and AI replace current jobs, new jobs will be created that will require the human touch. A TED Talk I recently listened to disspelled this and a couple other myths in a way which I had also been thinking and agreed with. Mainly, the key for me is this: past technological advances were still below human ability, but we're talking about computers that are SMARTER than people, far BETTER at tasks than people, and more SENSITIVE to situations than humans could possibly be. So my answer to that argument is that I think this time is different.

Don't think your job can be automated? "The Future of The Professions" details a long and well-thought-out research study that shows that most people see how every other profession could be automated, except their own. Maybe that's simple naivety regarding the complexities of other people's work, or maybe it's a little bit of ego that in fact gets in the way of seeing a realistic possibility. It also shows how even the most reputable and highest-paying jobs are being broken down into chunks that can be outsourced, off-shored or automated. This is the path towards technology unemployment.

Andy Stern, the former president of the Service Employees International Union, researched and wrote perhaps one of the best pieces on the future of employment and UBI called, "Raising the Floor: How a Universal Basic Income Can Renew Our Economy and Rebuild the American Dream." In his book, he takes the skeptical reader through the evidence that is pointing towards technological unemployment, and focuses a lot of his attention to the rapidly growing "gig economy," where people are now subsidizing their incomes or making their complete incomes via side-hustles like online stores and services and one-time jobs. I knew about some of the things happening in this space, having a small side-business of my own and having exposure to other areas like the sharing economy, but I was greatly impressed at the breadth of opportunities and functions that the gig economy now covers. Yet these things, too, can eventually be commoditized and automated to the point of being practically worthless to the gig workers.

So my ultimate challenge is this: How do we handle all this unemployment in the future, if not with universal basic income? In his dystopian fictional book "Manna: Two Views of Humanity's Future", Marshall Brain paints a picture where the welfare system just grows in efficiency and volume, absorbing more and more people as each job and profession become automated, making the welfare people's lives more and more miserable and giving them no way out of the system. And that does, indeed, feel like the inevitable future with the path we're on. He then poses an alternative which is a bit too sci-fi for my taste, but ultimately feels a little bit like a UBI-driven utopia.

I think my bend towards the belief in both technological unemployment / underemployment and UBI stems from a vision of a more balanced life. I've long been convinced that shorter work days and shorter work weeks was not only inevitable but highly desirable from both the employee and the employer standpoint. Namely, workers aren't really productive for 8 hours straight, or even 4 hours straight with a break. This has been proven time and time again with no contradicting data to my knowledge, yet we continue to act as if working longer hours means we're working harder or that we're more dedicated. This is absurd! When I hear of someone working 12 or more hours a day consistently, or working for 8 or 10 hours on the weekend, I shun them. Dedication to your job should be defined by your ability to manage your work time appropriately and then to shut it off and do things for yourself. Overworking yourself, working off-hours, working when you're tired could all lead to mistakes. In an office environment, if you're not sure of something, you can often ask a co-worker. But if you're working when everyone else has gone home or when you're supposed to be relaxing on the weekend, you have nobody to ask. So for the sake of getting something done, you go ahead and do it even if you're not sure. Then you find out on Monday morning you did it wrong, and have to undo or redo your work anyways.

And it feels like weekends are always too short. Friday night I'm just completely exhausted from the week and don't want to do anything productive, I barely want to do anything entertaining if it requires effort, or, you know, putting a bra back on. Saturday I'm still recuperating, wanting to do something fun and relaxing. I sleep in a little, we go for a walk, we eat good food, I clear my head. Sunday I start being productive, but before long, it's time to go to bed or I won't get enough sleep for my oh-so-important Monday. If only I had one more day to finish whatever I started on Sunday and get a little more rested before having to go back to work.

Some have argued with me that if I had a 4-day work week, I'd get used to it and think that a 3-day weekend was too short, and then if we had a 3-day work week, I'd again want it to be shorter. I agree that greed is a real thing and presents such a danger, but I adamantly disagree with the principle that we'd never be content with a work schedule. I think highly-motivated individuals want to work, at least in a place where they feel both challenged and valued, but that over-working people causes these otherwise ideal employees to burn out.

I don't know exactly what the "right" work schedule is, but I believe that there is a balance that can be struck somewhere that optimizes human productivity (and I believe it's less than 40 hours per week). Maybe it's four 8-hour days, or maybe it's three 9-hour days. Maybe we ditch the 7-day week schedule, and go to a three day on, three day off schedule. Maybe, it's variety that we need: we work a 9-hour day in one job one day, the next day go to a different 9-hour job, repeat each once more, than have a three-day weekend. Maybe one of these jobs is analytical, and the other is creative. Maybe one job has more physical activity embedded in it, and one has more brain-power requirements. Maybe we rotate between three jobs: physical, analytical and creative. Going down this path starts to look more and more like making a living solely via the gig economy, and I'd be lying if I said it wasn't an appealing idea.* But then there's the uncertainty of the gig economy, and the certainty of a paycheck and healthcare. So I do my best to keep myself to a 40 - 45 hour work week, and do not permit myself to work on the weekends or on vacations, and I call that the best balance I can do for now.

Regardless of what the "right" work schedule is, we're clearly not there right now. I've always felt that by the time I got home from work on a typical week day, I was too exhausted to do things like exercise, cook a healthy meal, read, write, take a class, paint, etc. In fact, often times I felt like the only thing I was capable of after work was watching TV and eating junk food on the couch. Sound familiar? I know for a fact that I'm not alone in this notion. No wonder America has an obesity problem! So I said, okay, I need to get up earlier to go for a run in the mornings. Cool! I did this. But there's only so much you can cram into your morning before your boss expects you at your corporate job. It felt like I was constantly faced with a choice: do I want to work on my physical health, my mental health, my side business, my artistic side, or my education?

Because I couldn't do all of them, nor could I even do more than one at a time. I went back to school, and gained weight. I started working out consistently, and didn't write for three months. I started working on a book I wanted to write, and fell behind on my reading. There's just NOT enough time in the day if I have to work 40 hours per week (which is really 45 - 50 hours in a typical week) with a typical hour of commute time minimum unless I forgo sleeping and showering altogether.**

Because I couldn't do all of them, nor could I even do more than one at a time. I went back to school, and gained weight. I started working out consistently, and didn't write for three months. I started working on a book I wanted to write, and fell behind on my reading. There's just NOT enough time in the day if I have to work 40 hours per week (which is really 45 - 50 hours in a typical week) with a typical hour of commute time minimum unless I forgo sleeping and showering altogether.**So there I was, already feeling like my corporate work schedule was far too overbearing in my life, not willing to take the plunge into the gig economy or some semblance of entrepreneurship without a steady paycheck, but still also believing that a good education, hard work and dedication is what was needed to succeed in this world. After all, I did work hard to get to where I'm at. I also do not take for granted the fact that I had the opportunity to go to college full-time, and that I was able to get a student loan to fund grad school as well. I am grateful for those and all the many other opportunities that helped shape my intelligence and academics, my creativity, and perseverance and my personality. So my success is a combination of opportunity and seizing it, executing my dreams with hard work and perseverance, and making good decisions that have opened up other doors of opportunity.

I held a bias against homeless people that they just want handouts without working for them, that they made bad choices over and over again to have gotten to where they are, or that they are mentally ill. For all of these reasons, handing them a couple bucks or giving them my leftovers never felt like it would do any good. I always had a small, deep desire to help them, but to actually help them, not to just get them through the next hour or the next day. I envisioned something of an educational shelter, like a rehab but for job training and personal finance skills, with the hope that they would leave the program better people and not return to poverty. But the cost would have to be astronomical, I thought. So I continued to work hard and climb that corporate ladder in hopes of maybe one day being able to afford such a program. I guess it wasn't a novel or original idea - as soon as I found a charity that does much of this, I immediately started donating a good amount of money to that charity and still do to this day. This, to me, was helping the poor and homeless.

It was within this backdrop that the concept of UBI struck a chord with my initially. I thought education, work ethic, intelligence and creativity were basically a formula for success - that you could always find a job if you had these things. As a conservative, I believed in a smaller government, less handouts and taxes, and letting the market determine the economic value of labor and things. At first pass, UBI sounded like a ridiculous liberal pie-in-the-sky pipedream.

Perhaps one of the most compelling points in favor of UBI was an idea from a TED Talk that first really turned my head on the topic, that "the effects of living in poverty... [is] comparable to losing a night's sleep or the effects of alcoholism." It's not that poor people are stupider or lazier than middle-class workers, or that they have bad luck. They make bad decisions because it's like they're too tired and dazed to see the long run - they're so overwhelmed with the burden of this financial hardship that they are unable to make the decisions that would get them out. I may be explaining that poorly so forgive me for my errors here, but that's how I understood it. And I get it! This makes sense to me - I have seen it all too many times with people who are really struggling financially. The poorer they are, the more short-term thinking they apply to get themselves out of this immediate problem without considering the long-term, assuming they will find a way to make it work in the long run, but then they don't, and they have this vicious cycle. Or maybe they know they won't be able to get out of the long-term problem, but they are procrastinating on fixing it because they feel pressed by the urgency of this short-term problem.

The conclusion of this TED Talk was, "Poverty is not a lack of character. Poverty is a lack of cash." An example I've heard somewhere, anecdotally as it might be, was of handing homeless people $1000 each, and that little bit of seed money was used to turn their lives around. If an average panhandler is given just enough to buy food for the day, maybe get a motel room a couple times a week to shower and sleep and wash her clothes, she'll never get ahead. But give her $1000 all at once, and she can rent a small apartment for a couple months, buy nutritious food, maybe a new outfit, maybe a bike to get to work in, and could get a job that would actually allow her to support herself on an ongoing basis. It's not a case of giving a man a fish versus teaching him to fish, they know how to fish, it's about giving the homeless and poor the fishing rod and a place to store and cook the fish. Don't give them fish, give them the ability to fish themselves!

Let's not worry about how to fund a Universal Basic Income just yet, and instead just assume that everybody in America got a minimum $11,490 per year, or $23,550 per 4-person family (if you're wondering where these figures are coming from, I just googled poverty line in America and am using that as the minimum). There are no conditions other than being an American resident, no requirement to work or contribute to society or have a basic education. Some people would inevitably choose not to work, and that's okay. A single mother might use that money to quit her second job and spend that much more time with her family. Someone else might go back to school instead of working his second job. That writer who felt stuck waiting on tables might finally quit her job and write that novel. A woman with an aging mother might retire early to take care of her mother and spend more time with her kids, now in college and starting their own families. An aspiring entrepreneur might use the extra bump to invest in the startup he's dreamed of getting off the ground while maintaining his full time job. Corporate employees might use the new bump towards their kids' college education or for better vacations. A person feeling burnt out in her job might use the extra income for more massages, or maybe it gives her just enough of a cushion to seek out a better opportunity. All of these options are okay.

And yes, there may be some people who use it in ways we think are bad - an alcoholic may buy more booze, a prostitute might be pressured into giving up her share to her pimp, I'm not even sure I can think of the worst case scenarios, but I don't want to pretend that it's all sunshine and rainbows. That's the thing with having no conditions on it, its use is based on free will. Generally, though, I think it would be good - it gives people opportunities to take risks, to better themselves, to spend more time doing what they want and less time making a buck, and it can open doors for the entrepreneurs and dreamers and artists to create new innovations and works that will ultimately make society a little bit better in their own ways. Imagine eradicating poverty and homelessness - now that's helping the poor!

Let's go back to our newspaper scenario from the beginning. Newspapers could be free and still maintain reputable journalists if the journalists wrote not for money but because they loved their jobs. Editors could still edit, because they have a UBI to fall back on, and maybe they do other things that make more money but they also spend some of their time editing. The key to accepting UBI as an option, I think, is separating livelihood from holding a job. Healthcare, too, for that matter. For so long it's been engrained in our thinking that if we get a good education and work hard, we will be successful. But college grads are finding fewer jobs available to them, and having to settle for jobs that don't require degrees. Young adults are moving back in with their parents to save money. Raising the minimum wage curtails retail stores and restaurants from hiring younger people with no experience.

If we take technological unemployment or underemployment as a reality, then as jobs disappear, we need to separate a living wage and basic healthcare needs from doing low-paid jobs. This is not a redistribution of wealth like in socialism, nor is it a welfare system where only the neediest get money. This is an unbiased payment to all that will open more doors and provide opportunities for people to better themselves, whatever that means to them. The capitalist economy will still work on top of the UBI - the middle-class can still make money to keep them well above the poverty line, and the top 1% will still be rich. The title of Andy Stern's book is exactly what it is, it's "Raising the Floor," not lowering the ceiling or putting everyone on the same level. I don't think we'll ever be 100% unemployed, I think we'll do fulfilling job and gigs and combinations of things that make money, but that those earnings will sit on top of the minimum UBI instead of being the only money we have to live on.

Funding a UBI seems daunting at first, but rest assured, there are a lot of people much smarter than me thinking about these things and running real numbers. But for the sake of accountability to show this line of thinking isn't completely cray-cray, I did some of my own math. I googled the population of the US and got 325.7MM people in 2017. Since I gave two figures earlier, one for a single person and one for a family of four, I'll average those two per person figures together.

($11,490 + $23,550) / 5 = $7,008 per person (Kids need less money than a single adult because they don't pay rent, those darn kids!)

Multiply that figure by the number of people in America in 2017, and rounding up, we get $2.3 trillion. That's an astronomical figure. But what do we spend today on other programs?

According to a quick search I did, I found that the Obama budget proposal in 2017 included $1.39 trillion in Social Security, Unemployment & Labor, $1.17 trillion in Medicare & Health, $179 billion in Veterans' Benefits, $109 billion on Food & Agriculture, $109 billion on Transportation, not to mention $303 billion on Interest on Debt. Let's assume that the UBI replaces Social Security, Unemployment & Labor completely - that takes care of more than half of our requirements, bringing the balance down to $910 billion that we need to cover. For the sake of this exercise and without knowing any detail, I will assume some of the Veterans' Benefits could be taken care of with UBI, so let's chop that in half, bringing our need to $820.5 billion. Under a long-term UBI society, we will have opportunities to take better care of our mental and physical health, so let's say we chop the Medicare & Health budget by 25%, bringing our total down to $528 billion.

Automation should make transportation and food & agriculture more efficient, so I'm going to take 50% from both of those budgets, bringing us down to $404.5 billion. I'm not sure what goes into Housing & Community, but I would think the UBI would cover some or all of this, let's assume all for this purpose, bringing us down to $314.5 billion. That's less than half the military budget, but I'm not going to chop there (although it's definitely a possibility), and it's just a hair over what we were going to pay in interest on our debts in 2017. I feel like we're so close here, we can taste it. Maybe we raise a little bit in property taxes or a little in corporate taxes or tariffs or something. As a conservative / kinda Republican, I hate all of those options, by the way, but they are a reality, since I hate a growing national debt even more.

All this to say, I don't have the complete picture or all the answers, but it's not as unyieldy or unreasonable as a number as it may seem. If we cut the benefits in half, it would be more than covered by the Social Security, Unemployment & Labor budget alone, with no other changes to the budget or taxes or anything else. Maybe we start there and see what we can do about the debt interest and other areas where efficiency and automation could help, to get us to the full benefit I proposed.

Alright, so we've played out a lot of hypothetical scenarios here, and I know you've had to suspend some of your beliefs or concerns in order to play along. I will ask you now to suspend nothing - question the math, question the theory, question why poor people stay poor, question why the rich get richer. I've linked to a number of great resources that I've found, and here's perhaps one of the most compelling findings of my little research: I've not found anything to persuade me that this is wrong. I want these things to be proven wrong, both technological unemployment or underemployment, and that a Universal Basic Income would work. But the arguments against them that I've found are so weak and unfounded, almost laughable. I can find more compelling "evidence" that you shouldn't vaccinate your child than evidence or arguments showing that UBI won't work. Maybe it's not big enough to attract the naysayers yet, I'll buy that for now. But it's gaining momentum after hundreds of years of idlely hanging out on the fringe, and this may be the generation to see it happen.

One more thing to think about; I briefly alluded to the minimum wage earlier. While I think UBI or something very similar could be a solution to technological underemployment, I would differentiate it vastly from the minimum wage. People fight for a livable minimum wage, and I think this is the wrong approach. A minimum wage, by definition, is the minimum a person could be expected to be paid. A teenager living with her parents and with no kids of her own, working a part-time retail job with no previous experience does not need to make enough to support a family of four. That is to say that if you are supporting a family of four, you should not be making minimum wage. Now, I get it, there's a cycle of poverty that keeps that working single parent down or whatever the case may be. But I believe teenagers have a right to work for crappy, non-livable wages to gain experience. Hell, some college grads take unpaid internships for experience. By raising the minimum wage, I believe we are only depriving these inexperienced young people the experience they need to get the next job up. This is where the "magic" of UBI comes in to play - if we instituted UBI roughly as outlined here, we could actually lower the minimum wage and let market forces do more of the driving on hourly rates. This is because that minimum wage would no longer be the sole income of any adult, ever! Every adult would get enough to stay out of poverty without working. They should be able to afford minimal housing, three meals a day and clothes and supplies. That means if they want to take a minimum wage job to make more money, to live in a slightly nicer home or eat slightly more interesting food or have slightly nicer things, they can, and if they want to go to school in hopes of maybe getting a better job in the future, they can, and if they want to stay home with the kids, they can. Then those poor teenagers can go to work for their crappy pay and get that experience while living with their parents and not having kids of their own, and I think that is a damn good thing indeed.

*Footnote:

I've criticized myself harshly at times for being too unfocused - I love so many things, from crafting and interior design to finance and economics, from technology and entrepreneurship to language and culture and travel. Imagine if I actually quit my corporate job and worked in the gig economy: spend an hour designing a logo for a client, then an hour teaching English via video chat to a student in China, take a break to work out, and then spend two hours writing a report for the Associated Press, and call it a day, or work on something else. If it weren't for the uncertainty of the gig economy and the certainty of my paycheck and health insurance, I'd do this right now. It sounds so much more fulfilling than my 9-to-5 that's really 7:30-5:30-ish-with-a-half-hour-lunch-break-if-I'm-lucky-instead-of-the-hour-lunch-break-we're-supposed-to-have. The path to this type of gig-based lifestyle just feels so risky still, but maybe it will be less so in the future. Or, maybe I'm delusional, and the cost of burn out from my corporate job is much higher than I know, and I could be spending my time better in the gig economy. How does one know?

**Footnote:

I took my recent job relocation as an opportunity to change my lifestyle such that it naturally incorporates more physical activity and minimized my commute. Specifically, I live so close to my new office that it makes no sense to drive, so I walk to work and also to shopping and restaurants for the most part. Thus, I naturally walk a lot more than I used to without having to think about traditional exercise. Plus, I have about an hour back each day from my commute, which helps with the balance of my personal time. It still takes monumental efforts, at times, to do things like coursework, reading, writing, art, and actual working out, but those other steps have given me more time to motivate myself.